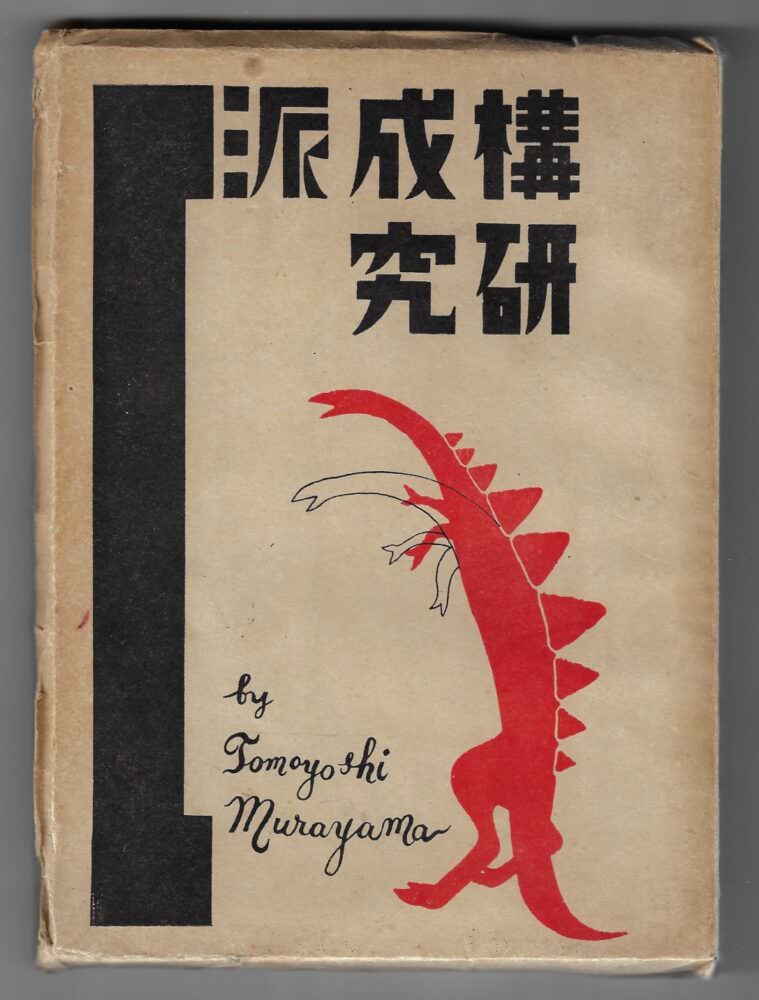

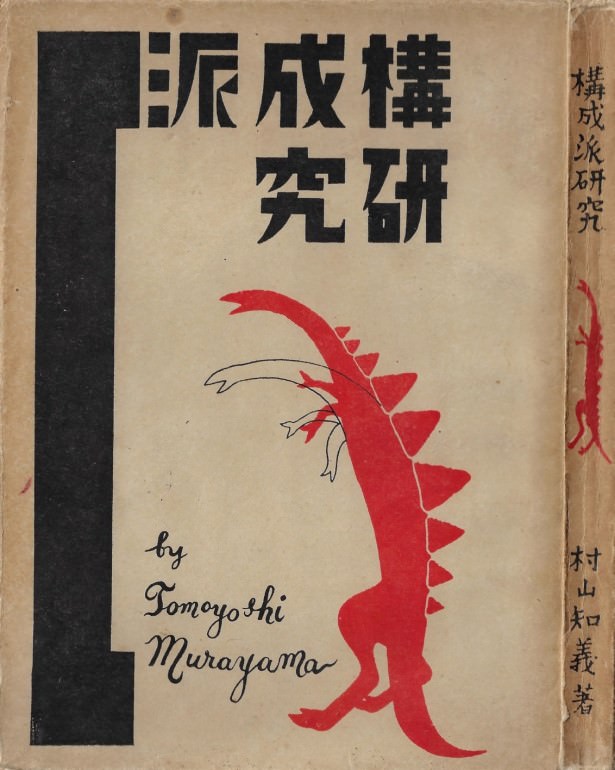

Kōseiha kenkyū (構成派 研究). [Study of Constructivism].

1926

verkauftMurayama, Tomoyoshi (村山 知義).

Kōseiha kenkyū (構成派 研究). [Study of Constructivism].

Tokyo, Chūō Bijutsusha, Taishō 15 [1926].

(2), 2, 6,pp., 32 plates with illustrations, 81, (2)pp., 3 pages of advertisements.19,5 x 14 cm. Publisher’s illustrated wrappers.

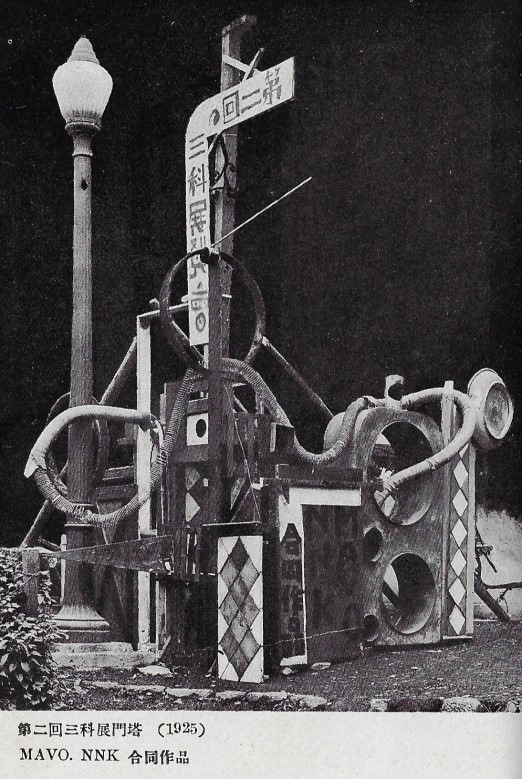

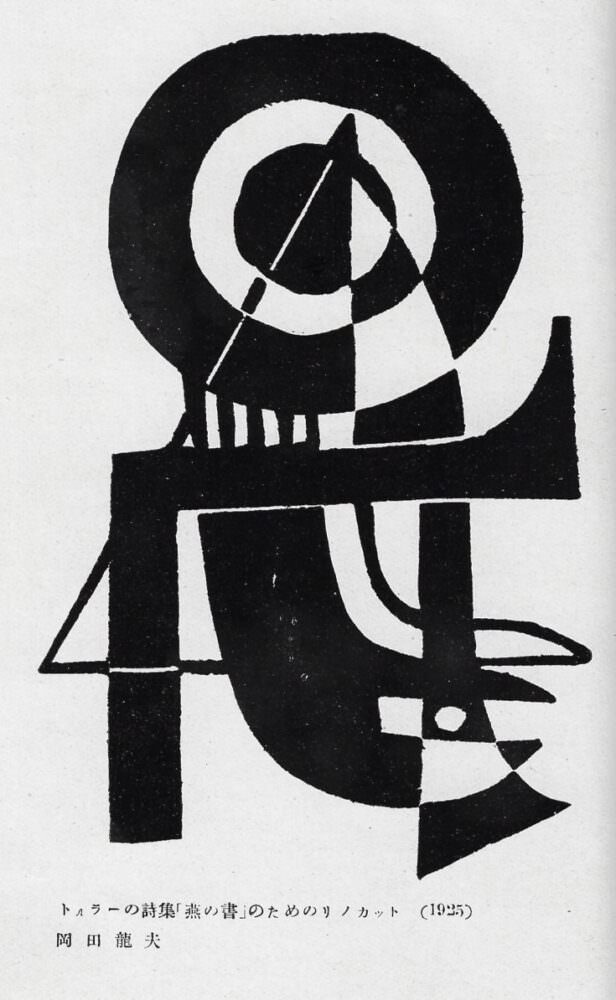

First issue, first print, in the same year two more prints were published.This book is an important document for the transfer of the European avant-garde to Japan and its adaptation to the Japanese Mavo movement. It is Tomoyoshi Murayama’s (1901-1977) second publication after his European journey (1922/23) and is devoted to the Constructivist elements of the art movements in Europe at that time.

The Japanese avant-garde that emerged in the Taisho period can be exemplified by two major movements: the Futurist Art Association (1920-22) and Mavo (1923-25). Although the course of the two groups paralleled Futurist and Constructivist movements in Russia, we must understand it for its distinctive characteristics rather than its interpretation of foreign concepts. In practice, Japanese avant-garde movements placed less emphasis on theoretical frameworks than their Western counterparts. Many artists participated in both groups and their style shifted over time rather than abruptly. Consequently, the works produced by the members of the two groups often cannot be visually distinguished even though the two groups touted distinctive artistic foundations

Before establishing Mavo in 1923, Tomoyoshi Murayama completed a brief but formative stint in Germany where he absorbed an impressive array of avant-garde practices in less than a year. Originally intending to study Christianity while abroad, Murayama quickly changed his focus when he found himself immersed in the avant-garde art circles in Berlin. The self-trained Japanese artist frequented Galerie der Sturm, attended avant-garde dances and theatrical performances. Upon his return to Japan, Murayama quickly formed an alliance with the newly disbanded Japanese Futurists. In his solo exhibition, mounted shortly after his return to Japan, Murayama launched an artistic formulation called “Conscious Constructivism,” which can be loosely described as a combination of Dada, Expressionism and Constructivism. Murayama never concretely explained his concept, but the term derived from Wassily Kandinsky’s writings. Murayama wrote on Kandinsky more than any other Western artist and he even earned the nickname “the Kandinsky of Japan.” He adopted the Russian painter’s ideas on breaking down the boundaries between art and life, but criticized some of Kandinsky’s ideas for their ambiguity. Even though no evidence points to an actual dialogue between Murayama and Kandinsky, the former was able to refine his theoretical formulations in writing through an imagined discourse with the Russian artist. Freely quoted after: Yang Wang, 2009, Russia Constructed: the Practice of Avant-gardism in Taisho-era Japan, 1912-1926.

The overlapping margins of the cover slightly creased as usual, cover slightly browned, all in all a very above average beautiful copy of the first impression of the first edition